What happens when we try to value what financial ledgers can’t capture

by SHI Director, Ann Armbrecht

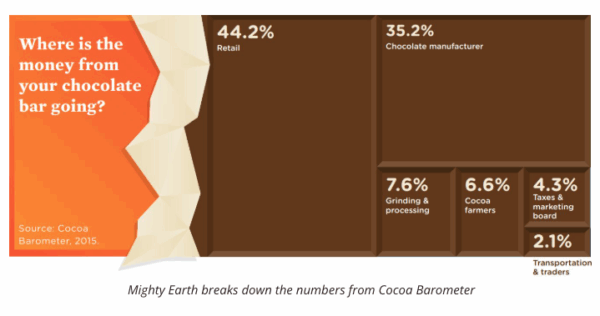

In 2015 the Cocoa Barometer provided a breakdown of where the money for a chocolate bar actually went. Images were created to illustrate this breakdown, which showed that 44% went to retailers and only 6.6% to cocoa farmers. The image was widely shared in articles highlighting inequities in the cocoa supply chains.

When I first started the Sustainable Herbs Initiative (then Program), Sebastian Pole, Josef Brinckmann, Mark Blumenthal, all leaders in the herbal products industry, and I discussed creating a version of that graphic for something like a box of chamomile tea. We talked about the design for a few moments, but then Josef pointed out that there is far more nuance and complexity than we could ever communicate on a box. Traditional Medicinals, the company where he worked, for example chose to keep its manufacturing in the United States. This cost more than if they outsourced it. But how could you communicate that? The box would just lead to simplistic and inaccurate judgements and accusations. And so, we dropped the idea.

The Limits of a Financial Ledger

Several years after the conversation about the box of tea, in a SHI Working Group meeting of Primary Processors, the ten or so participants from primary processing companies around the world, discussed important topics to focus on. Money kept coming up as central to every other topic, especially, how raw material prices were set and by whom, what those prices did and did not include.

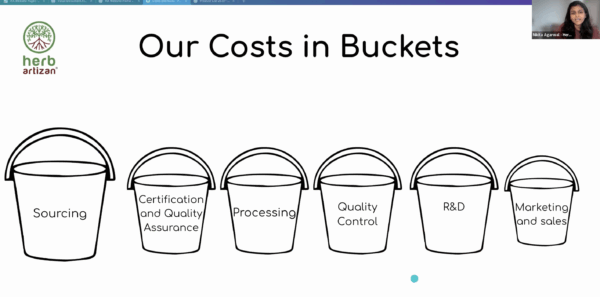

We spent the next four or five meetings with participants sharing the visible and invisible costs that go into producing the raw and semi-processed botanical material that their companies buy and sell. Each shared how they track these costs and how they try to bring them into negotiations over pricing. Nikita Agarwal created a graphic illustrating the buckets that Herb Artizan uses: sourcing, certification and quality assurance, processing, quality control, R and D, marketing and sales. Sourcing was the largest bucket, marketing and sales the smallest.

As Paulo Barriga from Pebani said, if we don’t price the material accurately, we can’t continue to invest in our business, and we won’t be able to stay in operation. Too often the market sets prices for raw material in trade not the costs of production.

Seeing Double

The priests and shamans in Hedangna, a village where I lived in northeastern Nepal, talk about ‘seeing double’, seeing the visible and the invisible (in their stories, the ancestors). They tell a story about how humans who can’t see double, who can only see what they can hold in their hands, what is concrete and visible with their eyes are ‘selfish.’

On a fundamental level, in sharing these visible and less visible costs, we were trying to help each other ‘see double.’ Each of the speakers shared what their company invests – time, resources, expertise, attention, care, and more – in producing the products their company produces. These investments, very difficult to quantify in financial terms, contribute to what literary philosopher, Robert Pogue Harrison, calls the ‘laral’ value of a thing – or the quality which buyers who come to these companies seek.

Yet, because these herbs are bought and sold in a competitive market, that value must be translated into a monetary value. By discussing those invisible values, we hoped to make it easier for them to be recognized in negotiations over price, at least for the companies in this conversation.

Multi-stakeholder Views on Cost

We took this discussion to the whole SHI member community at the October monthly meeting. Five stakeholders representing companies from source to shelf shared the visible and invisible costs they hold: Paulo Barriga from Pebani, a primary processor in Peru; Nikita Agarwal from Herb Artizan, a primary processor in south India; Danielle Kruse from Trout Lake Farm; Matt Richards from Organic Herb Trading Company in the UK; and Ian Brabbin from Yogi.

There are fixed costs, those are easier for companies to name even though many of them are also invisible and are difficult to track. These include providing inputs like seeds and compost for farmers, driers for wild harvesters, fuel for running drying and processing equipment, etc.

But beyond fixed costs, there were costs in terms of attention, care, and expertise that proved even harder to value.

The ROI of Relationships

The hardest cost to quantify are relationships. Each speaker spoke about the work that goes into creating and maintaining relationships, relationships with wild harvesters, with smallholder farmers, with primary processors, with buyers. These relationships are crucial when there are shortages, or crop failures, or problems with testing and samples or shipping, or any number of problems that come up, which they inevitably do, in shipping container loads of botanicals around the world. Yet the time invested in creating relationships is difficult to quantify.

Yogi has a line item for supplier relationships and travel, rare in this industry where companies often view supplier visits as an investment they can’t afford, because getting to know the farmers with whom they do business is a core value for Yogi.

Someone asked if they had an ROI (return on investment) for that. “We don’t look at it that way,” Ian explained. “We focus on a strategic supply chain, looking at 5 years in future, identifying projects we can do together, strengthening that relationship, seeing what we can create together. It’s hard to put the ROI on that.”

Thirty Three Certifications

Certifications are often cited as a way to bring more revenue to producers. However, the true cost of certifications can be hard to capture in financial terms. Herb Artizan maintains 33 different certifications – each requiring audits, fees, paperwork, and on-the-ground ongoing verification with farmers to ensure practices are being followed.

These certifications offer assurance that certain practices around caring for the plants and people are being followed, assurance that is essential for companies who care about these values but don’t have direct relationships with their suppliers. But Matt Richards from OHTC explained, buyers who care about these values are often not willing to pay the additional costs investing in them requires. As a company, OHTC invests in some certifications even if they don’t have buyers who will pay the additional cost because of the assurance the certification provides OHTC around human rights and other practices followed.

Longterm Health versus Short Term Profit

Long-term investments often conflicted with short-term returns. Trout Lake Farm can get a higher return on root crops versus aerial parts. But it isn’t good for the soil to keep digging roots and so, investing in long-term soil health means lower income in the short run.

Nikita said that the two things that matter both for the farmers in their farmer networks are getting a guaranteed purchase and fair pricing. They provide both of these. They also support farmers transitioning to organic, often they pay farmers in advance when their buyer’s place orders. Yet their own buyers often don’t pay them for 30, 60, or even 90 days after receiving the material. Herb Artizan has to bear the financial cost of the gap.

Marketing

It can be easy to judge marketing costs for brands. I continue to be surprised when companies have five to ten people in marketing and only one or two responsible for sourcing 30-150 raw materials from around the world. But as Ian, the one speaker from a brand, said, companies can’t ignore marketing. None of the investments these companies want to make in improving social and environmental conditions and paying higher prices matter if they can’t stay in business. “Just to tread water in a highly competitive market is a big investment,” Ian explained. “It costs even more money to try to grow.”

Making the Invisible Visible

In the discussion that followed, everyone commented on the value of this type of transparency, especially around money. Zacharia Levine from The Synergy Company observed that this level of transparency is unparalleled in most industry circles. He thanked the speakers for operating from that place of trust.

Ian Brabbin said, “We are all responsible for the future of our industry.” But that requires first seeing and understanding what each participant is holding and investing, where they need support and where they can do a little more. And then, once these are more visible, to together discuss how to offer that support and help better distribute the costs, the risks, and the benefits.

To me, conversations like this are also a way of squinting my eyes. I try to be like the priests in Hedangna, seeing beyond what my eyes can see, sensing into all that goes into the value of that object, all that can never be reflected in the price. By practicing, we can perhaps strengthen this muscle so that we are more easily able to see the invisible costs of any item we purchase and, with time, begin to shift the system overall so that it truly supports what we value.